Read the Original Elle Magazine Article Here

The process of collecting a rape kit—that is, gathering evidence of a violent assault from a person’s body shortly after the crime was committed—is an impossibly sensitive one. But Julie Groat is an expert. She is a forensic nurse and program director at Wayne County SAFE, a nonprofit that was founded in 2006 to focus exclusively on providing care to sexual assault survivors.

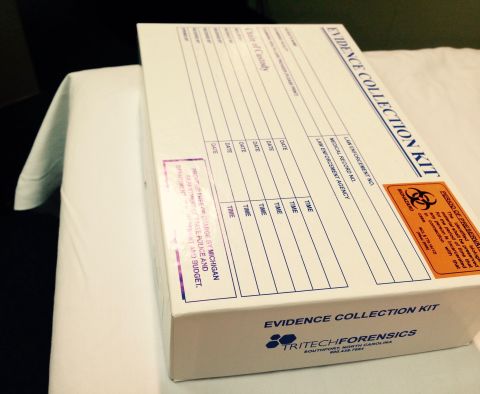

Its first decade has been a dramatic one. In 2009, 11,341 untested rape kits were found in a Detroit police warehouse, leading to a long and still-ongoing battle for justice. A Michigan law enacted in 2014 now mandates a timeline for moving the kit from health care provider to various levels of law enforcement—three months from start to finish. It also requires that health care providers notify victims of their right to receive information about their own kits.

This process begins at the front door of SAFE. At their clinic in Taylor, Michigan—one of five in the Detroit area—Groat walked me through the process, beginning from the moment when there’s a knock on the door.

Can you talk about when the patient first arrives?

Everybody is greeted. I always have our young patients introduce me to whoever they bring. It empowers them. I introduce myself and then I say, “Well, who did you bring?” I may already know—I’ve got the reporting on who mom and dad are—but I want them to tell me. It also lets the parents know that [their child] is in control.

We then excuse ourselves from the family and ask the patient to come to the back room, where we go through the medical history and the incident. You only write what the patient tells you, even if you know more about what’s going on. Everybody processes differently; she may forget some things that happen. I’m not going to pick and choose.

I’m also not going to rush the patient. She’s going to go at her own pace. If she needs a break, she needs a break. I know parents sometimes want [their child] to have these exams. Well, it’s up to the patient. It’s a very invasive procedure. We don’t want to re-victimize anybody by making them go through something that they don’t want to go through. Power and control has already been taken away; you want to give that back to them.

What happens when you’re treating patients?

We’re focusing on how the information pertains to our diagnosis and treatment. We’re not investigative. Knowing what color of car was driven is more for the police.

A head-to-toe assessment is conducted, follwed by a detailed genital exam with a colposcope, [a device that allows us to] magnify and take pictures of the genital area. We do hair combings and collect underwear or whatever clothing they’re wearing. Also collecting swabs as we go. Based on the patient history, we know where to swab, but we go beyond that. Even if it was a vaginal assault, we still get anal swabs, because gravity will pull [fluids] into that area.

Listening is the most important thing we do. Many years ago, there was a serial rapist, and during one of the patients’ histories, she said that there was licking of the breast; so we swabbed the breasts of the victims. We wouldn’t have done it otherwise. The DNA we found there was only gathered because we listened to the patient.

At Avalon, we offer the STD and pregnancy prophylaxis as a standard component of care. We follow-up with our social work staff. I explain to my patients, you may not be ready today, you may not be ready tomorrow, maybe not next week or in a month, or even a year. But the services here are always free and we encourage you to take advantage of them.